Some extraordinary gardeners like Virgil Severns and Terry Reichardt have been growing winter squash in Alaska for years, but for us ordinary gardeners, it’s becoming a much more reliable and feasible crop.

If you’re gardening for food security, squash is a great option because you can store it without having to freeze or can it (and incidentally, you should NOT can pumpkins or squash at home according to the National Center for Home Food Preservation, but you can can cubed winter squash). Storing as is saves time during the mad dash of fall when we are trying to cook and eat all of the fresh produce from the garden or preserve what we can’t eat; as well as pick berries, fish and hunt. Not only does winter squash actually provide some calories as opposed to greens, it is paleo friendly, gluten free, delicious and nutritious. If you don’t have the space to grow squash, you can find locally available winter squash here.

Varieties

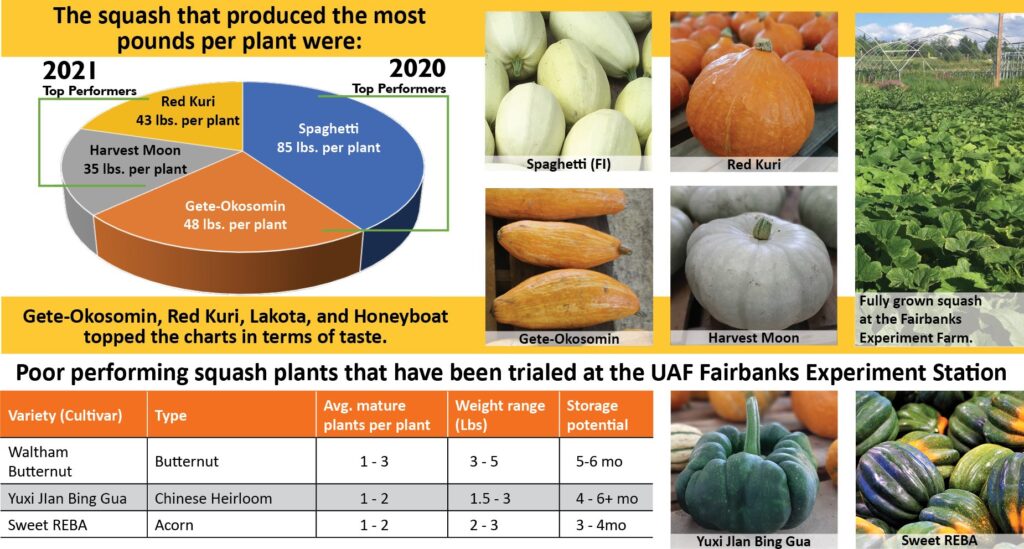

In Fairbanks some varieties are performing incredibly well in variety trials. In 2020, spaghetti squash yielded 85 pounds per plant while Gete-Okosomin produced 48 pounds per plant. Harvest moon and Red Kuri performed best in 2021, producing 35 and 43 pounds of squash per plant, respectively. Gete-Okosomin, Red Kuri, Lakota, and Honeyboat topped the charts in terms of taste.

This year, 12 varieties of winter squash are being trialed in Fairbanks, so stay tuned for those results. Winter squash performed a lot less well in unreplicated trials at the Matanuska Experiment Farm. Glenna Gannon, director of the vegetable variety trials figures it could have been that Typar landscape fabric or infrared transmitting or IRT plastic was not used, the temperature is cooler than Fairbanks, and the transplants were not fertilized. She thinks a hoop house or high tunnel could make all the difference in successfully growing winter squash in the Matanuska Valley or cooler parts of Alaska.

Acorn, butternut, delicata, and sweet dumpling squash are sensitive to long days and as a result, do not reliably produce female flowers, particularly in the more northern parts of Alaska.

This poster provides even more information on the variety trial results.

If you have the space, plant your squash in a different spot each year to minimize diseases and pests. You’ll want to use one or more season extension techniques to grow the winter squash — plastic mulch, low tunnel, high tunnel, or a greenhouse. In Fairbanks trials, the squash is planted in infrared transmitting mulch with the space between rows covered in typar. The typar helps minimize rotting by keeping the squash clean and it also helps produce a lot of heat, too.

In rainier parts of Alaska, low tunnels, high tunnels or greenhouses are important to protect the squash from the rain and heat up air temperatures.

If you have a small space like I do, consider planting one or two plants of the bush or semi-bush varieties like Pinnacle (spaghetti squash), Bonbon, or the Gold Nugget bush variety. These can be spaced 1.5 to 2 feet apart in rows with the rows 6 feet apart. For the long vining varieties, you will need to space plants 2 to 3 feet apart, with rows 12 feet apart!

Harvest

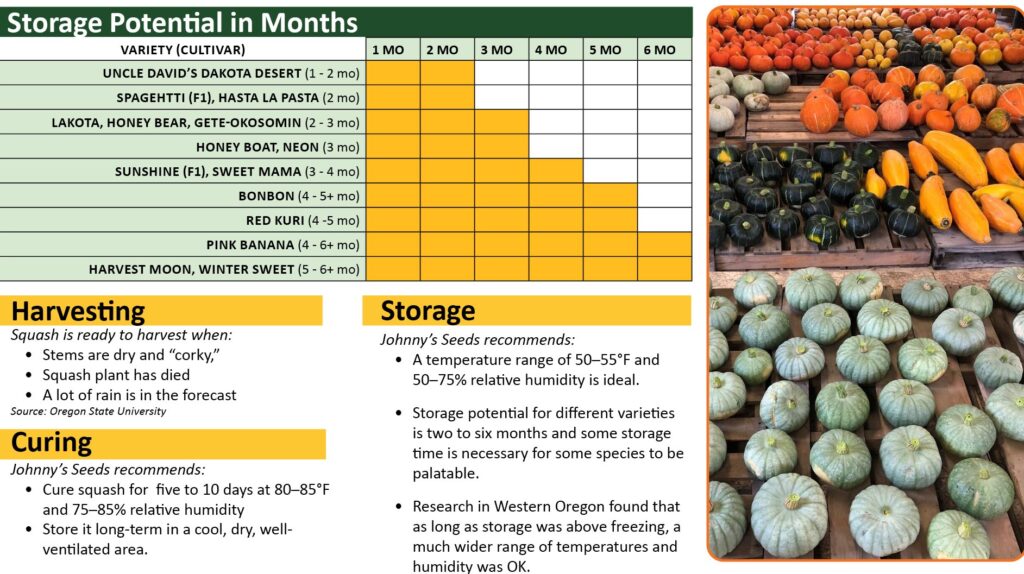

According to Oregon State University, squash is ready to harvest when stems are dry and “corky,” the squash plant has died, or a lot of rain is in the forecast.

Curing and storage

Johnny’s Seeds recommends curing squash for five to 10 days at 80–85°F and 75–85% relative humidity, then storing it long-term in a cool, dry, well-ventilated area. For storage, a temperature range of 50–55°F and 50–75% relative humidity is ideal. Storage potential for different varieties is two to six months and some storage time is necessary for some species to be palatable. Research in Western Oregon found that as long as storage was above freezing, a much wider range of temperatures and humidity was OK.

Cooking squash

One of the hurdles with eating winter squash is chopping it up. The Eat Winter Vegetable Project suggests using a chef knife at least 8 inches or larger, cutting the end of the squash to create a flat surface, then slicing the squash vertically on a cutting board. If it is slippery, use a towel on the cutting board to keep it in place. They also have some helpful videos to show the various techniques of chopping, cooking and peeling squash.

Personally, I’ve found that if I cut off the ends, make holes with a fork, and microwave it for about three minutes (more for large squash), it makes peeling and chopping the squash much easier. A couple of my favorite recipes are Squash and Leek Gratin With Maple Syrup And Pistachio Crumble and Squash Toasts with Ricotta and Cider Vinegar.

Additional Information

Oregon State University has some excellent videos, recipes, as well as growing and storage information about different varieties, as well as a more in depth look at Kabocha and Buttercup squash (these types grow well in Alaska). Johnny’s Seeds compares storage potential, average squash weight, and vine length in this chart.

Previously published in the Fairbanks Daily Newsminer July 24, 2022.